The woman unfurled herself from the silk rope, dropping gracefully as she unwound over about 10 feet. The movement was so controlled and sinuous it appeared effortless. She twirled there, some 20 feet off the ground.

I was at an interview for an article on Austin’s Blue Lapis Light, a site-specific aerial dance company, watching rehearsal (here’s that article: “Art, Athleticism Shine in Blue Lapis Light Performances”). The dancers perform original shows, harassed to rigging, dropping over a rooftop’s edge to twirl and dance across the face of a building or underneath highway bridges.

Their current performance, Edge of Grace, takes place on and around giant scaffolding erected at the nonprofit’s new site. It’s a really thrilling show, and that element of risk — OMG! I could never do that! — transforms artistic expression into athletic spectacle. You just can’t look away.

One Person’s “Safe” is Another’s “Sorry”

Risk is a recurring theme through sports and athletics. For the trained aerialist, that unfurling of silk while dropping toward the floor was second nature, a movement so practiced as to have become ingrained. Untrained, nonprofessional me — I’d plummet, a screaming bag of rocks to splat on the practice mat.

Risk is a recurring theme through sports and athletics. For the trained aerialist, that unfurling of silk while dropping toward the floor was second nature, a movement so practiced as to have become ingrained. Untrained, nonprofessional me — I’d plummet, a screaming bag of rocks to splat on the practice mat.

The level of risk decreases with the amount of skill, education, and familiarity. In other words, one woman’s “safe” is my “sorry.”

The risk/skill continuum is a slippery relative slope. When I started running, a 10K (6.2 miles) was as far as I could imagine. But that comfort level kept getting pushed and pushed, and before I could say “Pikes Peak,” I had moved beyond the marathon, up mountains, off the road, and into the wilderness. One icy February, I even found myself taking on a 100 miler.

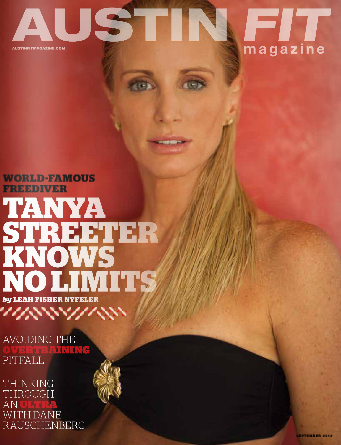

One of my favorite articles from my Austin Fit Magazine days was a Sept. 2012 cover story I wrote on a world champion freediver: “Tanya Streeter Redefines Limits — Her Own and Yours”

Streeter is an amazing woman: articulate, passionate, easy to connect with, and accomplished. She also happens to be skilled at holding her breath for an incredible amount of time. Streeter’s 2002 No Limits freediving world record set the bar for women — and men — at 160 meters (525 feet) and took 3 minutes and 26 seconds. Others have since died attempting to surpass her feat, and the record still stands for women.

“I don’t minimize the risk,” Streeter recalled in our interview. “Don’t forget, I woke up every morning with a huge safety team who reassured me, who we’d handpicked. And we studied safety and put procedures in place that hadn’t been used before. We looked at what the rules called for and quadrupled it. We did everything to make it safe. So I didn’t believe that what I was doing was risky.”

This excellent June 2015 New York Times article, “Lost Brother in Yosemite” by John Branch, brought my thoughts back to Streeter and the idea of risk. The story recounts the final BASE jump of Dean Potter, 43, and Graham Hunt, 29, both experienced athletes who’d made that same leap many times. BASE is an acronym — building, antenna, span (bridge), and Earth (cliffs) — describing the places from which athletes launch jumps. Potter and Hunt were also wing-suit flying; something went wrong in the jump, neither man deployed his safety parachute before crashing, and both died.

They loved what they were doing, practiced the sport, and took every precaution — except not jumping.

Who Decides What is Too Risky?

Clif Bar rocked the climbing world with its Nov. 2014 announcement that it would no longer sponsor several athletes due to the risk associated with their sports, primarily free climbing and BASE jumping. Potter was one of those released. Outside quoted Potter as pointing out the hypocrisy in dropping the athletes at the same time the company had sponsored and was promoting a documentary, Valley Uprising, that featured all five climbers and jumpers (“Why Clif Bar Fired 5 of its Top Athletes”).

Clif Bar rocked the climbing world with its Nov. 2014 announcement that it would no longer sponsor several athletes due to the risk associated with their sports, primarily free climbing and BASE jumping. Potter was one of those released. Outside quoted Potter as pointing out the hypocrisy in dropping the athletes at the same time the company had sponsored and was promoting a documentary, Valley Uprising, that featured all five climbers and jumpers (“Why Clif Bar Fired 5 of its Top Athletes”).

Was Clif Bar right to drop those athletes? It’s hard to say, and Potter’s death months later makes it easy to agree with the business’s decision. But who decides what level of risk is acceptable? Clearly, being dropped did nothing to stop Potter from participating in the sport he loved so much.

And what does “acceptable” mean? Is BASE jumping less acceptable because risks are more visible than, say, football, with its easily camouflaged brain damage? Is free climbing less acceptable because the chance of falling to horrific injury or death is more gruesome than the known spectacle of watching two MMA athletes kick and hit each other over a set period of time?

Who decides?

Right now, I can’t imagine rock climbing, much less free climbing (notice I said “right now,” because I’m tempted to try rock climbing someday). I’ve drawn the line at bungee cord jumping and flat out refused to set foot into Austin’s indoor skydiving facility. For me, the risk of a spinal cord injury outweighs any desire I have to learn more about the activity. I made that choice.

But plenty of people question my choices in the sports I do. My dad told me I was “borderline stupid” for doing an Ironman; a good friend has called me crazy for continuing to run after my freak snowstorm experience in Pocatello; and there are those who have expressed consternation about my upcoming Grand Canyon trip. Let’s not even get into conversations about boxing.

I don’t see the same risks. I know what my body can (and can’t) do, I spend lots of time testing gear and fine-tuning my practices, and I work to hone my skills constantly. Like Streeter, I do everything in my power to make sure I put my best foot forward at every event.

But that’s not to say that, in an instant, circumstances can’t change. Despite endless preparation and practice, something can always go wrong. No one can predict, say, the guy who drives 13 miles down the toll road at 80mph going the wrong way; shit happens. Few of us would say that getting in the car each day is a risk…and yet many of us have accidents, some die.

There’s no way to prepare for and prevent all of life’s randomness. I accept that risk in pursuing the sports I love.